Article of the Month - December 2020

“Athens”

(Martin Devecka: Assistant Professor Classical Studies,

University of California Santa Cruz)

Martin Devecka, "Athens," Broken Cities: A Historical Sociology of Ruins (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 2020), chapter 1, pp 10—36.

Article Abstract:

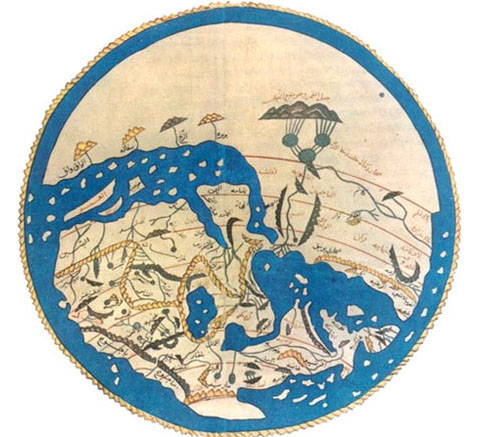

We have been taught to think of ruins as historical artifacts, relegated to the past by a catastrophic event. Instead, Martin Devecka argues that we should see them as processes taking place over a long present. In Broken Cities, Devecka offers a wide-ranging comparative study of ruination, the process by which monuments, architectural sites, and urban centers decay into ruin over time. Weaving together four case studies—of classical Athens, late antique Rome, medieval Baghdad, and sixteenth-century Mexico City— Devecka shows that ruination is a complex social process largely contingent on changing imperial control rather than the result of immediate or natural events. Drawing on literature, legal texts, epigraphic evidence, and the narratives embodied in monuments and painting, Broken Cities is an expansive and nuanced study that holds great signiZcance for the Zeld of historiography.

Keywords: Athens, Greece, antiquarianism, ruins, empire, colonialism, identity

Nomination Statement:

“Athens” is the first chapter of Martin Devecka’s book Broken Cities: A Historical Sociology of Ruins (Johns Hopkins, 2020), “a history in four parts of how urban civilizations in Western Eurasia and the Americas has come to grips with the apparent fact that cities are ruinable.” Challenging an understanding of ruins inherited from Renaissance antiquarianism, Devecka draws on written accounts in a wide range of genres to show how the discourse on ruins or the threat of ruination illuminates significant civilizational differences. “Athens” interrogates the very notion of “ruin” by introducing temporality as a crucial variable and shows how ruins and ruination were political and rhetorical tools of anti-democratic forces in ancient Greece. Subsequent chapters examine the discourse of ruins and ruination in the cases of Rome, Baghdad, and Tenochtitlan. The contrast between “Athens” and “Rome” underscores the discontinuities within what we might be tempted to see as “classical antiquity” while “Baghdad” expands the frame of late antique Mediterranean culture.

Author’s Comment:

This chapter comes out of a book that stems from my longstanding interest in “the past of the past.” The book, Broken Cities, uses cross-cultural comparison to show that different societies, at different times, have construed ruins in different ways. What unites these construals is that, taking place against the background of urbanism, they get deployed in debates about the future of cities. Within those debates, the ruin is a representation that can bring into being what it represents. In this context, Classical Athens presents a paradox: a literature full of ruins, a landscape where they are absent. Depictions of ruins in Classical Greek rhetoric are prospective, expressing anxiety about the future with reference to certain events—the Persian Wars, the Peloponnesian War—which could have produced permanent ruins but did not.

In making those claims, I aim to revise a set of unconscious assumptions about the meaning of ruins that have tended to guide (or mislead) classicists writing on the topic. These assumptions have had a distorting effect on our view of ancient Athens more generally. Scholars who take it for granted that ruins always serve a memorializing function have been overly credulous about the authenticity of historical documents (the so-called “Oath of Plateia”) and over-hasty in interpreting ambiguous archaeological finds (the remains of the older Parthenon in Pericles’ new construction). We can gain a better appreciation of these things and others by keeping in mind that the Greek view of ruins is different from, perhaps incommensurable with, our own.

I also aim to situate Greek thinking about ruins in the context of broader Mediterranean engagements. Ultramarine colonization and migration are key to the formation of Athenian ruin concepts in particular, while an ocean-crossing story of revenge is the model within which Athenians understand their own avoidance of ruination and justify their creation of ruins elsewhere. Greek encounters with the Mediterranean world help us understand how the Greeks could develop a concept of ruins that was so at odds with more local historical experience.

Would you like to discuss this article?

Start a thread on the Mediterranean Seminar list-server

See the other Articles of the Month here.